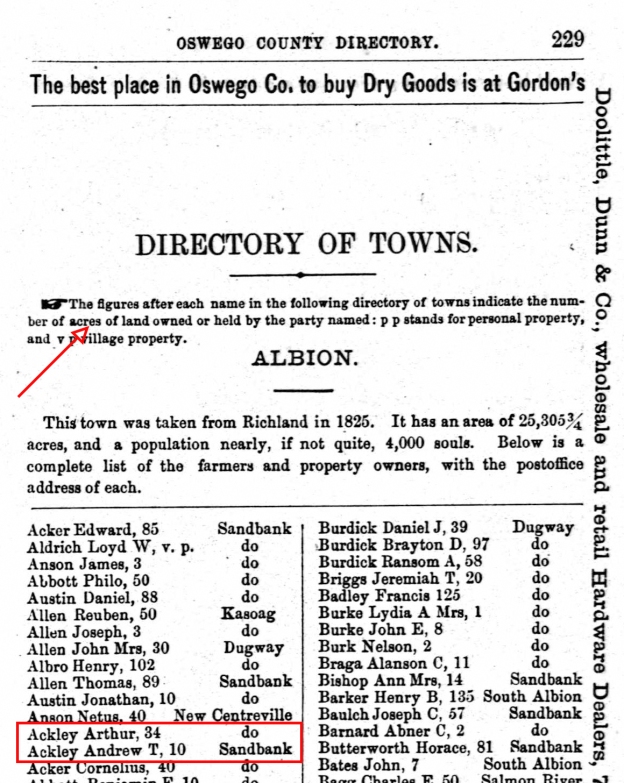

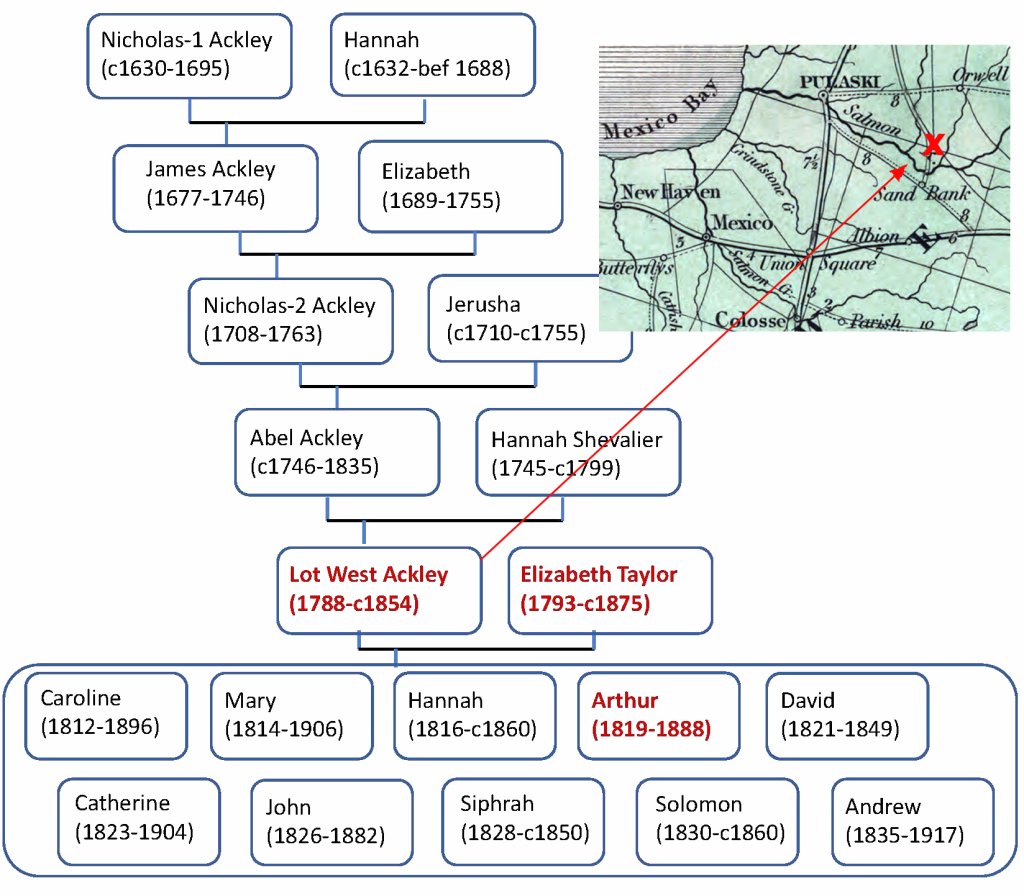

Lot West Ackley (1788-abt 1854) definitely got the Ackley “adventure gene.” Born in 1788, six months before the birth of the USA, he married an 18-year-old Elizabeth Taylor (1793-abt 1875) in Washington County, NY in 1812. In 1813, he moved with Elizabeth and their infant daughter 160 miles west to Sand Bank, Oswego County, NY. The area was truly a frontier at the time, even more so than Haddam, CT when Nicholas-1 relocated there in 1667. A few other families from Washington County relocated to Sand Bank at about the same time as Lot and Elizabeth, but the total population could not have been much above 30.

In 1831, Lot and Elizabeth bought property just north of town and settled in. By 1835, they had ten children–and their oldest daughters had married and were starting their own families.

Lot died before an 1854 map of the area was drawn. Elizabeth appears as owner of the property that year and is listed as a widow in the 1855 census. She lived for another 15-20 years with one or another of her children, either on the farm or close by.

This chapter traces the lives of Lot and Elizabeth, setting them in the context of events of their time. It includes several appendices with greater detail. These summarize the lives of each of the ten children; trace participation in the Civil War of seven of their descendants; summarize the available censuses for Lot and Elizabeth; and list the most common errors about them that appear in online family histories.

See the Nicholas’s Descendants page.