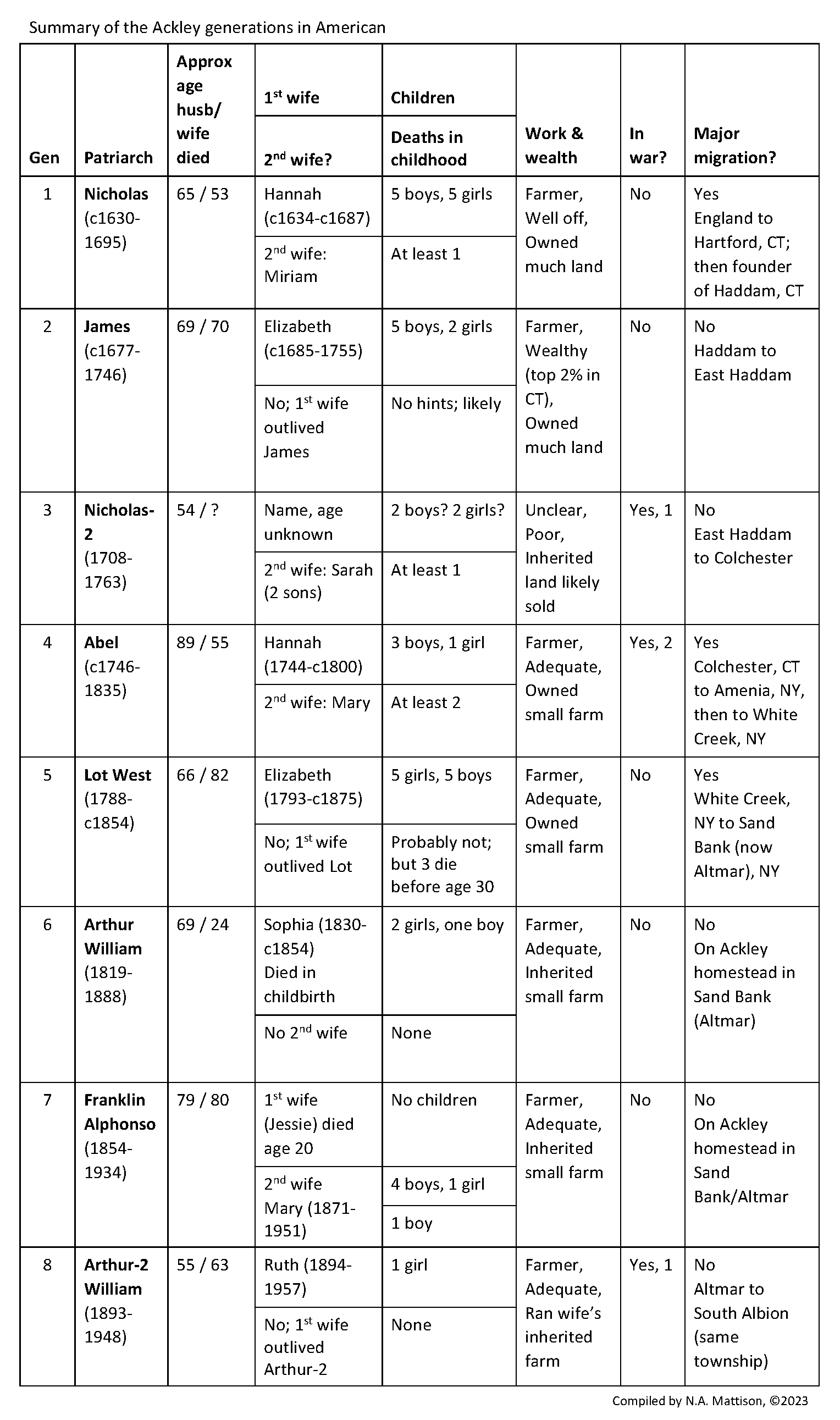

Below is a brief overview of the first eight generations of my direct line family of Ackleys in America (and only that line). Note that the table and the summary below do not include references because these are available in the chapters that explore the earlier generations. Please see those for both references and detailed explanations about the research and findings. (This post may be downloaded as a pdf file by clicking here.)

The adventure gene

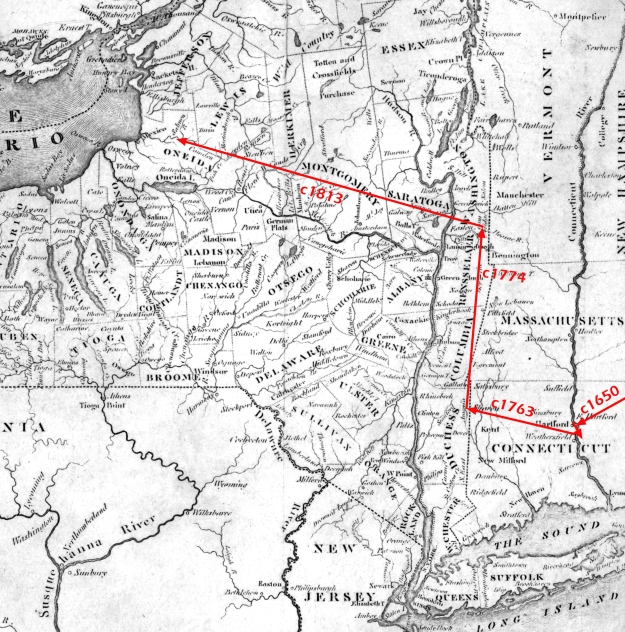

Nicholas arrived in Hartford, CT in about 1650, less than two decades after its founding. The town was some distance from Boston, which then was the largest city in the northeastern English colonies, and two or three days’ journey from the towns in the south on Long Island Sound. By the time Nicholas married about 1655, life in Hartford was settled—laws were in place, commerce thrived, and the sense of community was strong. But Nicholas left that behind in 1667 to help found what would become Haddam, CT, more than a day’s hard trip away, with about two dozen other families. It was wilderness but offered the prospect of more land and potentially more wealth.

Nicholas’s son and grandson, James and Nicholas-2, did not have the wandering spirit. James moved across the Connecticut River to East Haddam and Nicholas-2 to the adjoining town of Colchester. But Abel, next in line, certainly got the adventure gene. In about 1764, at the age of about 17, he and his younger sister, both recently orphaned, left Colchester for the new town of Sharon, CT. That town was then on the frontier, about 80 miles west. Abel had relatives and friends there, and probably no other good option for himself or his sister. They married siblings and settled across the border in Amenia, Dutchess County, but Abel did not stay. In about 1774, he moved his wife and children about 90 miles north up the Hudson River to what is now White Creek, Washington County, NY.

Two of Abel’s sons led settled lives in Washington County, NY, becoming prosperous farmers, but the youngest son inherited that adventure gene. With his young wife and infant daughter, Lot West Ackley headed west in about 1813, settling 170 miles away in Sand Bank (now Altmar), Oswego County, NY. At the time, it was complete wilderness and he was among the first arrivals. The next three generations stayed in the area.

The migrations were gutsy, for sure, but all were to areas with family or friends. Nicholas likely chose Hartford in part because a group of men also from County Essex, England already was there. Similarly, many of the early settlers of Sharon, CT were from the area of Colchester, CT and Abel had relatives there. Abel also was not alone on the next move: Washington County attracted many from Dutchess County, NY including two Ackley cousins. Forty years later, Lot headed west to Sand Bank at the same time as several other families from Washington County.

Modest lives, comfortable enough

For the most part, the Ackleys were moderately successful farmers, except James, who was in the top two percent of the wealthiest men in CT in the early 1700s. Nicholas-2, his son, probably was not a farmer, but plied a trade such as carpenter or stonemason. He seems to have struggled in life and was the only man in the line to appear to be destitute at his death.

Several Ackley men were involved in local politics and government over the generations; none was particularly prominent. They were the type of family essential to the building of the country—the essential, honest, reliable middle class.

None of the Ackleys appears to have been charged with a crime, although James and his wife were sued for slander by his sister. This family feud is now famous, sadly, as the last time supposed witchcraft was part of a court case in CT (see post here).

Patriotic, but not attracted to war

Some generations in this line participated in wars, some did not. Two of Nicholas’s sons probably fought in the first French and Indian War at the end of the 1600s. Nicholas’s grandson Nicholas-2 and at least two of his sons were in the militia in the last French and Indian War in the mid-1700s. One of those was Abel, who also fought in the Revolutionary War, albeit briefly. His son Lot is rumored to have served in the War of 1812, but likely did not. Two of Lot’s sons (but not my direct line) enlisted at the outset of the Civil War, surviving that horrible conflict but with lifelong injuries. Two Ackley brothers in the eighth generation, including my grandfather, enlisted in World War I—just days before the fighting ended. By the second World War, these men were in their 40s and 50s, and not called up.

Marriage, family and the lives of women

The Ackley men throughout the years married fairly late, some in their mid-to-late 30s. This was not unusual for their times. Men in four of the seven generations of Ackleys married a second time, after the death of a first wife. In most of the generations, the family was created with the first wife and the second was a mid-life marriage. Nicholas-2 did have two sons (not direct line) with a second wife and Frank’s first wife died childless at age 20. Second marriages were common through the generations. Women had few options for supporting themselves; those who were widowed remarried and as soon as possible.

Two Ackley first wives in the earlier generations did outlive their husbands: the wife of wealthy James, who had no need to remarry, and the wife of fifth-generation Lot, whose eldest son supported her. By the 20th century, women remaining unmarried widows was more common: the second wife of Frank outlived her husband as did Arthur-2’s wife and neither remarried.

Until the mid-1800s, most women appeared in records after they married only with their given names, making them virtually impossible to research. Records for both women and men are sparse for the first five generations. The US censuses began in 1790, but it was not until 1850 that the given names of wives and children were recorded. Until then, only the name of the head of household was recorded and the rest were counted by age range and gender.

Good information is available only on one woman in this line before the 1800s: Hannah Shevalier who married Abel in the mid-1700s. A descendant of her father published a well-researched history of that French Huguenot family. After Hannah, the next woman with traceable ancestry is Sophia, who appears by name in the 1850 census. Her family, the Mattesons, arrived in Rhode Island in the mid-1660s (her cousins were my paternal ancestors). Mary, in the seventh generation, was the daughter of Irish immigrants who married into a family whose ancestors had arrived from Holland in the mid-1600s. Her ancestry is explored in the chapter on Frank and Mary. Not being able to trace the other women leaves many questions maddeningly unanswered.

Whatever their ancestry, these were tough and brave women who ran households that required substantial amounts of hard labor just for daily living. Yet they still produced a baby every two to three years for 20–25 years. Until the late 1800s, large families were essential not only to completing the chores of daily life but also to creating and maintaining the overall wealth of the family.

Lengthy but precarious lives

Most of the Ackley men in this line lived long lives for their times. Nicholas died at about 65, which was average for men in his generation in that area of CT; James lived to be about 69; Nicholas‑2 died comparatively young at 54; Abel lived to an amazing 89; Lot to 66; Arthur to 69; Frank to 79 and Arthur-2 to only 55.

Of course, age at death tells us nothing about the quality of life in later years. Medicine for much of this time was rudimentary, and these men would have suffered, perhaps greatly, from ailments and conditions we routinely treat today. This would have been true for the entire family through all generations, and for much of their lives.

Women did die in childbirth, an event often not recorded as such. The only known such death in this direct line was Sophia, my second-great grandmother who died after giving birth to Frank on 31 December 1854. The other wives were past child-bearing age at their deaths, except perhaps Nicholas-2’s first wife, who remains unidentified.

Almost every Ackley generation lost at least one child in childhood. Knowing exactly how many in each generation is impossible before the late 1800s because records for births and deaths were simply not well kept. Children who had died before their fathers died usually did not appear in the father’s probates or wills, of course; official records contained births and deaths only if the parents reported them, which they often just did not do; and many records have been lost over the years. Relying on family lore for such information may mean that children who died young often are simply forgotten by later generations.

The two earliest Ackley generations lost fewer children and experienced fewer deaths from disease than later generations. This was primarily because those early generations were more isolated. As the population, travel, commerce, wars and immigration increased, so did the spread of disease. It is too easy for us in the 21st century to forget that it was after World War II—in the eighth generation and into the ninth—when antibiotics became widely available, effective treatments for heart disease were developed, vaccines for killer childhood diseases appeared, and death from complications of childbirth became uncommon. The complex medical care we take for granted today would have seemed like the wildest of fiction to the first eight Ackley generations in America.

The story of this Ackley line, then, is part of the story of the settlement and development of America and the USA. The chapters on each generation tell that story in greater detail, placing these ancestors in the context of their times. Although we never will know exactly what their lives were like, this approach makes the people in each generation more than just names and dates. That has been a major purpose of the chapters that trace the eight generations.

N.A. Mattison, ©2023