Censuses are a blessing and a curse for family historians. People become much easier to track and family members easier to identity beginning in 1850. That US census was the first to record the names and ages of everyone in a household. The earlier US censuses recorded the name only of the head of household; the rest were counted by age range and gender. In 1855, New York state (NYS) began its own censuses, also recording names and, that year, recording place of birth—county, if not the current county of residence, or state if outside NYS.

This should mean fewer mysteries, right? We now have place of residence, names, age and, depending on the census, other information such as place of birth and even place of parents’ birth. All this, we imagine, has been based on questions asked of a live person and then carefully written down on the spot.

If only.

Censuses are puzzle pieces, but they are only that. They were not intended to be completely accurate. The purpose was to enumerate the population as a basis for determining policies that provided services such as funding for schools or building infrastructure. A few errors just did not matter.

Census takers were sometimes, well, just awful. Some clearly found spelling a challenge; others (probably most) seem to have filled in data well after the interview, relying on illegible notes or faulty memory. Below are a few examples of what that can mean for the family historian.

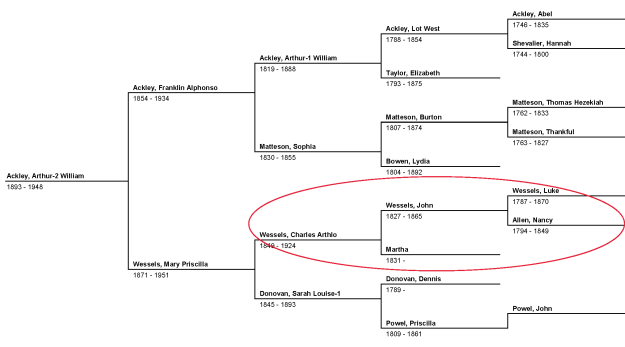

In 1855 NYS census, John Wessels lived in Mexico, Oswego County, NY and had four children. One was named Arthur but with a Dutch twist: Arthlo. In the 1850 census, the enumerator has written “Orthello,” adding a Shakespearean flavor to the name. The name never appears again because as a teen Arthlo understandably shoved that name to the middle and used just the initial. He became “Charles A. Wessels.” Figuring out this was the same man required eliminating other possibilities—fairly easy in this case.

Also in the 1855 NYS census, John is listed as being born in Herkimer County, a place I doubt he ever even visited. His parents lived in Orwell, Oswego County, in the 1820, 1830 and 1840 censuses. John was born about 1826. He had to have been born in Orwell; Herkimer was at minimum a two days’ journey. Information for some of John’s siblings confirm that they all were born in Orwell.[1]

So why Herkimer? The census taker may have asked John about his unusual name, Wessels, and where the family came from. In the discussion John may have mentioned that some Wessels had settled in Herkimer County—and that is the county the census taker remembered and wrote down. But even John’s father’s family did not live in Herkimer (see below).

That census also shows John as having lived in Mexico, NY for nine years. But in the 1850 census, five years prior, he is living in Ellisburg. His father had relocated the family to Ellisburg in 1842 and John married there about 1846.

When a census is this far off for one family, it is a safe bet that others in that locale also will have errors. And sure enough! Two of Luke’s stepchildren living in his household are incorrectly given his last name—and only ever in this one census.

In the 1865 census, John’s father Luke and second wife Sally are listed as being born in Oneida County. But Luke’s War of 1812 record, and the 1855 census, shows that he was born in Schenectady County. He was drafted in Schenectady County in the summer of 1812 and spent the last half of that year in Sackett’s Harbor, NY. He would have marched through Orwell on the way and evidently that is where he stopped on the way back, and stayed. (Sally probably was born in Oneida County since that appears more than once in her records.)

This list could go on. But the point is that it is important to rely on more than one source of information. Censuses were neither designed nor expected to be perfectly accurate.

The Wessels will be part of the chapter on Frank and Mary Wessels Ackley.

[1] See, for example, Chapman Brothers (1885), Portrait and biographical album of Whiteside County Illinois, Chicago: Chapman brothers, p. 273 on James Wessel.