In researching Discovering Nicholas Ackley, a number of myths and legends surfaced. In fact, the book was inspired by my determination to discover what most likely was true about Nicholas, and what was not.

Below is a baker’s dozen of the most common misunderstandings about Nicholas. Explanations for each are in Discovering Nicholas Ackley and also in some earlier posts on this blog (see links).

1. Nicholas most likely was born in County Essex in England, not County Shropshire. Many of the Hartford immigrants were from Essex and Nicholas was likely to have chosen Hartford for that reason. The Shropshire (Hopton Castle) connection is based on a genealogy that now is known to be fraudulent (see Nicholas Ackley and Gustav Anjou, Master Forger of Genealogies). It also is possible Nicholas was born in Holland to Puritan parents who were living in exile, as were many Puritans from the area of eastern England. He still would have been considered English, not Dutch, but it might explain his first name, which was unusual in England.

2. Nicholas’s parents are unknown. Those often identified as his parents are based on that same fraudulent genealogy and, for a number of reason, cannot be his parents. (See Nicholas Ackley and Gustav Anjou, Master Forger of Genealogies

3. Nicholas’s year of birth is about 1630. This fits best with events in his life and the laws and customs of the times.

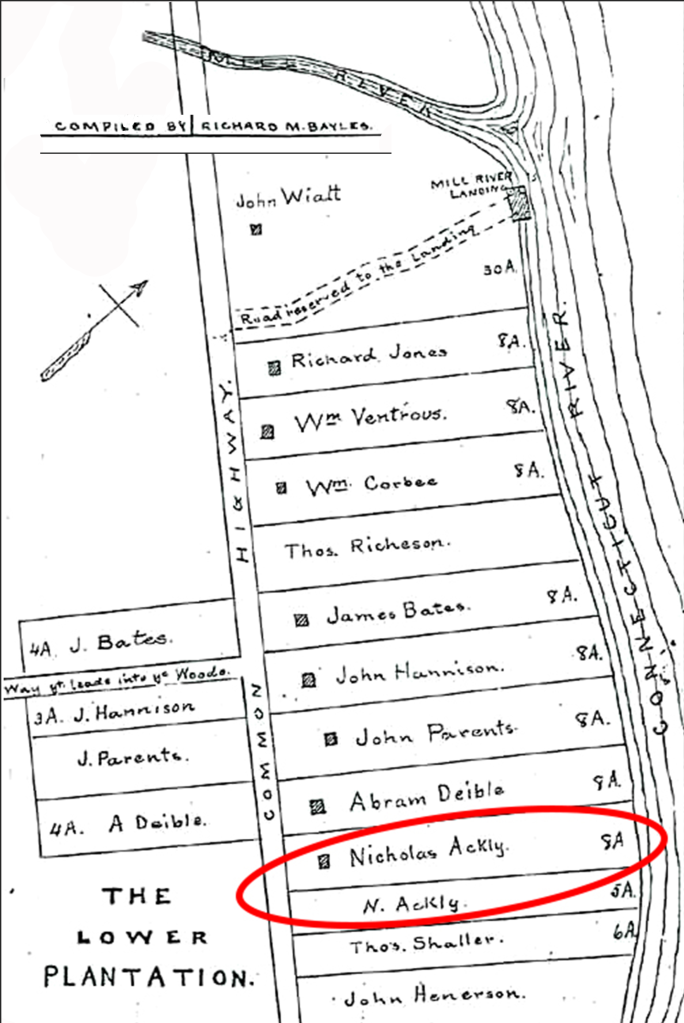

4. Nicholas likely arrived in Hartford about 1650. He signed a document in early spring 1653 (the Nonotuck Petition) so the latest he could have arrived was late autumn 1652. Few ships made the trip across the Atlantic in winter because it was too treacherous. In addition, ports often were iced in all winter since this was at the height of the Little Ice Age in Europe and North America.

5. Nicholas probably did not leave England to escape the English Civil War unless he was a Royalist and a member of the Church of England. But if he had been a member of the Church of England, he would have been unwelcome in Hartford and likely banned from living there. Only Puritans were welcome and those deemed “undesirable” were forced to leave.

6. Nicholas was probably not an indentured servant; it would have been rare in Hartford. He most likely was middle class—he could sign his name–and migrated for new opportunities and adventure.

7. Nicholas and Hannah probably married in 1655. Laws at the time required a man to be married in order to become a “householder,” and the first known listing of him as a householder is 1655.

8. Hannah’s maiden name is not known. Research on Ford and Mitchell as possibilities make it clear she likely was neither. (See Discovering Our Female Ancestors: Hannah and Miriam Ackley). In fact, it is not certain that her first name was Hannah but it does seem likely.

9. Nicholas’s second wife was a widow named Miriam, surname unknown. It was not Moore—that was a different Miriam. (See Discovering Our Female Ancestors: Hannah and Miriam Ackley).

10. Nicholas probably did have a son named Nicholas. It would have been rare for a family to not have a son named after the father. Nicholas and Hannah likely married in 1655 and the first known child was born about 1657. Hannah had at least 10 children, evenly spaced except for two gaps: the first between about 1662 and 1666 and the second between about 1666 and 1670, just after the move to Haddam. I suspect Nicholas Jr. was born after 1666 and before 1670. Childhood deaths were more common than they are today, from both accidents and disease.

11. Nicholas’s delay in moving to Haddam from Hartford was not unusual nor was he the only man who delayed. Men seem to have frequently changed their minds about being part of a new town; most of those who signed the petition to found Nonotuck backed out. But Nicholas did live up to his obligation in Haddam, just later than most others.

12. Nicholas is sometimes misidentified as being a “private,” but that designation was not used in the colonies until the Revolutionary War, eight decades after Nicholas’s death. He would have been part of the local militia, as were all men, but he did not have a military title and was not part of any “war.” His great grandson Nicholas #3 was a private in the Continental Line (the army, not a militia) during the Revolutionary War.

13. All of Nicholas and Hannah’s children were born either in Hartford or Haddam—none was born in East Haddam and Nicholas never lived in East Haddam. That town had not been settled by the time the last child, James, was born about 1677. Nicholas died in 1695 on the homestead in Haddam, which was sold three years later.

Considering that Nicholas lived nearly half a millennium ago, a remarkable amount of information is available about him. Although official records can be important, just as crucial to separating fact from fiction is an understanding of the laws and the customs of the time. Life was much different in Puritan Connecticut than it is in the US today and different from the simplistic Thanksgiving Day myth about the Puritans/Pilgrims that is so familiar.